Banking Act of 1933 (Glass-Steagall)

June 16, 1933

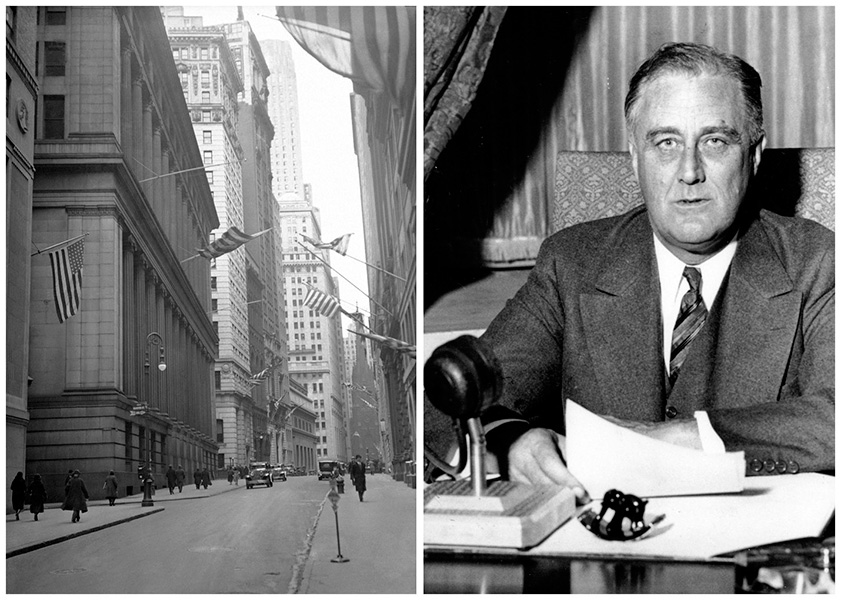

The Glass-Steagall Act effectively separated commercial banking from investment banking and created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, among other things. It was one of the most widely debated legislative initiatives before being signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in June 1933.

The emergency legislation that was passed within days of President Franklin Roosevelt taking office in March 1933 was just the start of the process to restore confidence in the banking system. Congress saw the need for substantial reform of the banking system, which eventually came in the Banking Act of 1933, or the Glass-Steagall Act. The bill was designed “to provide for the safer and more effective use of the assets of banks, to regulate interbank control, to prevent the undue diversion of funds into speculative operations, and for other purposes.” The measure was sponsored by Sen. Carter Glass (D-VA) and Rep. Henry Steagall (D-AL). Glass, a former Treasury secretary, was the primary force behind the act. Steagall, then chairman of the House Banking and Currency Committee, agreed to support the act with Glass after an amendment was added to permit bank deposit insurance.1 On June 16, 1933, President Roosevelt signed the bill into law. Glass originally introduced his banking reform bill in January 1932. It received extensive critiques and comments from bankers, economists, and the Federal Reserve Board. It passed the Senate in February 1932, but the House adjourned before coming to a decision. It was one of the most widely discussed and debated legislative initiatives in 1932.

Some background: In the wake of the 1929 stock market crash and the subsequent Great Depression, Congress was concerned that commercial banking operations and the payments system were incurring losses from volatile equity markets. An important motivation for the act was the desire to restrict the use of bank credit for speculation and to direct bank credit into what Glass and others thought to be more productive uses, such as industry, commerce, and agriculture.

In response to these concerns, the main provisions of the Banking Act of 1933 effectively separated commercial banking from investment banking. Senator Glass was the driving force behind this provision. Basically, commercial banks, which took in deposits and made loans, were no longer allowed to underwrite or deal in securities, while investment banks, which underwrote and dealt in securities, were no longer allowed to have close connections to commercial banks, such as overlapping directorships or common ownership. Following the passage of the act, institutions were given a year to decide whether they would specialize in commercial or investment banking. Only 10 percent of commercial banks’ total income could stem from securities; however, an exception allowed commercial banks to underwrite government-issued bonds. The separation of commercial and investment banking was not controversial in 1933. There was a broad belief that separation would lead to a healthier financial system. It became more controversial over the years and in 1999 the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act repealed the provisions of the Banking Act of 1933 that restricted affiliations between banks and securities firms.

The act also gave tighter regulation of national banks to the Federal Reserve System, requiring holding companies and other affiliates of state member banks to make three reports annually to their Federal Reserve Bank and to the Federal Reserve Board. Furthermore, bank holding companies that owned a majority of shares of any Federal Reserve member bank had to register with the Fed and obtain its permit to vote their shares in the selection of directors of any such member-bank subsidiary.

Another important provision of the act created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation![]() (FDIC), which insures bank deposits with a pool of money collected from banks. This provision was the most controversial at the time and drew veto threats from President Roosevelt. It was included at the insistence of Steagall, who had the interests of small rural banks in mind. Small rural banks and their representatives were the main proponents of deposit insurance. Opposition came from large banks that believed they would end up subsidizing small banks. Past attempts by states to instate deposit insurance had been unsuccessful because of moral hazard and also because local banks were not diversified. After the bank holiday, the public showed vast support for insurance, partly in the hope of recovering some of the losses and partly because many blamed Wall Street and big bankers for the Depression. Although Glass had opposed deposit insurance for years, he changed his mind and urged Roosevelt to accept it. A temporary fund became effective in January 1934, insuring deposits up to $2,500. The fund became permanent in July 1934 and the limit was raised to $5,000. This limit was raised numerous times over the years until reaching the current $250,000. All Federal Reserve member banks on or before July 1, 1934, were required to become stockholders of the FDIC by such date. No state bank was eligible for membership in the Federal Reserve System until it became a stockholder of the FDIC, and thereby became an insured institution, with required membership by national banks and voluntary membership by state banks. Deposit insurance is still viewed as a great success, although the problem of moral hazard and adverse selection came up again during banking failures of the 1980s. In response, Congress passed legislation that strengthened capital requirements and required banks with less capital to close.

(FDIC), which insures bank deposits with a pool of money collected from banks. This provision was the most controversial at the time and drew veto threats from President Roosevelt. It was included at the insistence of Steagall, who had the interests of small rural banks in mind. Small rural banks and their representatives were the main proponents of deposit insurance. Opposition came from large banks that believed they would end up subsidizing small banks. Past attempts by states to instate deposit insurance had been unsuccessful because of moral hazard and also because local banks were not diversified. After the bank holiday, the public showed vast support for insurance, partly in the hope of recovering some of the losses and partly because many blamed Wall Street and big bankers for the Depression. Although Glass had opposed deposit insurance for years, he changed his mind and urged Roosevelt to accept it. A temporary fund became effective in January 1934, insuring deposits up to $2,500. The fund became permanent in July 1934 and the limit was raised to $5,000. This limit was raised numerous times over the years until reaching the current $250,000. All Federal Reserve member banks on or before July 1, 1934, were required to become stockholders of the FDIC by such date. No state bank was eligible for membership in the Federal Reserve System until it became a stockholder of the FDIC, and thereby became an insured institution, with required membership by national banks and voluntary membership by state banks. Deposit insurance is still viewed as a great success, although the problem of moral hazard and adverse selection came up again during banking failures of the 1980s. In response, Congress passed legislation that strengthened capital requirements and required banks with less capital to close.

The act had a large impact on the Federal Reserve. Notable provisions included the creation of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) under Section 8. However, the 1933 FOMC did not include voting rights for the Federal Reserve Board, which was revised by the Banking Act of 1935 and amended again in 1942 to closely resemble the modern FOMC.

Prior to the passage of the act, there were no restrictions on the right of a bank officer of a member bank to borrow from that bank. Excessive loans to bank officers and directors became a concern to bank regulators. In response, the act prohibited Federal Reserve member bank loans to their executive officers and required the repayment of outstanding loans.

In addition, the act introduced what later became known as Regulation Q, which mandated that interest could not be paid on checking accounts and gave the Federal Reserve authority to establish ceilings on the interest that could be paid on other kinds of deposits. The view was that payment of interest on deposits led to “excessive” competition among banks, causing them to engage in unduly risky investment and lending policies so that they could earn enough income to pay the interest. The prohibition of interest-bearing demand accounts has been effectively repealed by the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010. Beginning July 21, 2011, financial institutions became allowed, but not required, to offer interest-bearing demand accounts.

Endnotes

- 1Glass and Steagall also cosponsored the Banking Act of 1932, which was also commonly referred to as the Glass-Steagall Act prior to the passage of the Banking Act of 1933.

Bibliography

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. “Banking Act of 1933.” June 16, 1933, https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/scribd/?item_id=15952&filepath=/docs/historical/ny%20circulars/1933_01248.pdf![]() .

.

Friedman, Milton and Anna J. Schwartz. A Monetary History of the United States 1867-1960. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963.

Meltzer, Allan. A History of the Federal Reserve Volume 1: 1913-1951. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

Preston, Howard H. “The Banking Act of 1933.” The American Economic Review 23, no. 4 (December 1933): 585-607.

Shughart II, William. “A Public Choice Perspective of the Banking Act of 1933.” Cato Journal 7, no. 3 (Winter 1988).

Silber, William. “Why Did FDR’s Bank Holiday Succeed?” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic Policy Review, July 2009.

Wells, Donald. The Federal Reserve System: A History. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2004.

White, Lawrence J. “The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999: A Bridge Too Far? Or Not Far Enough?” Suffolk University Law Review 43, no. 4 (August 2010).

Emergency Banking Act of 1933

March 9, 1933

Signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on March 9, 1933, the legislation was aimed at restoring public confidence in the nation’s financial system after a weeklong bank holiday.

“The emergency banking legislation passed by the Congress today is a most constructive step toward the solution of the financial and banking difficulties which have confronted the country. The extraordinary rapidity with which this legislation was enacted by the Congress heartens and encourages the country.”

– Secretary of the Treasury William Woodin, March 9, 1933

“I can assure you that it is safer to keep your money in a reopened bank than under the mattress.”

– President Franklin Roosevelt in his first Fireside Chat, March 12, 1933

Immediately after his inauguration in March 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt set out to rebuild confidence in the nation’s banking system. At the time, the Great Depression was crippling the US economy. Many people were withdrawing their money from banks and keeping it at home. In response, the new president called a special session of Congress the day after the inauguration and declared a four-day banking holiday that shut down the banking system, including the Federal Reserve. This action was followed a few days later by the passage of the Emergency Banking Act, which was intended to restore Americans’ confidence in banks when they reopened.

The legislation, which provided for the reopening of the banks as soon as examiners found them to be financially secure, was prepared by Treasury staff during Herbert Hoover’s administration and was introduced on March 9, 1933. It passed later that evening amid a chaotic scene on the floor of Congress. In fact, many in Congress did not even have an opportunity to read the legislation before a vote was called for.

Endnotes

- 1The gold standard was partially restored by the Gold Reserve Act of 1934. The United States remained on the gold standard until 1971.

Bibliography

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. “Documents and Statements Pertaining to the Banking Emergency, Presidential Proclamations, Federal Legislation, Executive Orders, Regulations, and Other Documents and Official Statements, Part 1, February 25 – March 31, 1833.” 1933, https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/scribd/?item_id=23564&filepath=/docs/historical/federal%20reserve%20history/bank_holiday/bank_emerg_pt1_19330225.pdf![]() .

.

History Matters, the U.S. Survey Course on the Web. “‘More Important Than Gold’: FDR’s First Fireside Chat.” Accessed September 30, 2013, http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5199/![]() .

.

Silber, William L. “Why Did FDR’s Bank Holiday Succeed?![]() ” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic Policy Review, July 2009, 19-30.

” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic Policy Review, July 2009, 19-30.